Butch Moss A wounded California Guard soldier served four combat tours. Now he's fighting the Pentagon

For the last three years, retired California National Guard Master Sgt. Bill McLain’s wife, Terese, has repaid a bit of his enlistment bonuses to the Pentagon with a caustic note. For the last three years, retired California National Guard Master Sgt. Bill McLain’s wife, Terese, has repaid a bit of his enlistment bonuses to the Pentagon with a caustic note.

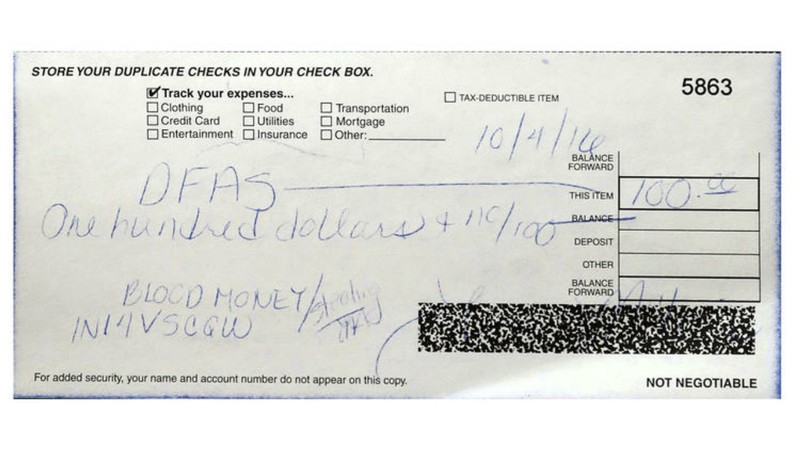

Each month, she writes “blood money” on the $100 check — the token amount the McLains pay on the $30,000 debt they deny owing — that she sends to the Pentagon. “Shame on you. Extortion,” she writes on the envelope.

The Pentagon cashes each check.

Facing a groundswell of public outrage, the Pentagon scrambled this week to temporarily suspend its demands for thousands of California Guard soldiers to repay enlistment bonuses and other incentives they were given to go to war. Facing a groundswell of public outrage, the Pentagon scrambled this week to temporarily suspend its demands for thousands of California Guard soldiers to repay enlistment bonuses and other incentives they were given to go to war.

But McLain and other soldiers who were wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan may still be required to repay their bonuses, one of several apparent exceptions in the proposed Pentagon solution.

Two weeks before McLain left to fight in Afghanistan in early 2013 — his fourth combat tour in a decade — the National Guard garnished his entire $3,496 monthly paycheck for the enlistment bonuses it claimed he was improperly given five years earlier.

“I had nothing,” the 55-year-old retired special forces soldier recalled Thursday about leaving his wife and two stepdaughters without his salary while he went back to war. “They took every nickel.”

McLain managed to get the wage garnishment lifted, but his troubles were just beginning.

The Pentagon has hounded him ever since to repay the bonuses, even after he was diagnosed as 90% disabled on account of head and back injuries sustained in combat, including a 2008 attack in Iraq when a roadside bomb nearly destroyed his jaw.

McLain is one of about 9,800 current and former California Guard soldiers who were ordered to repay enlistment bonuses, tuition assistance or other payments that officials said were improperly awarded when the Defense Department was frantically trying to fill its ranks for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A Los Angeles Times story last weekend that revealed the Pentagon repayment demands sparked a public furor about what many viewed as an injustice. Members of Congress and both major party presidential candidates expressed outrage and demanded action.

Under pressure to respond, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter interrupted his trip in Europe on Wednesday to announce a temporary suspension of the claw-backs. He pledged that a special review panel would consider each soldier’s case over the next eight months.

Carter said the Pentagon would grant debt waivers to soldiers who took the enlistment incentives and other payments without realizing they were ineligible. Some soldiers were given as much as $60,000, officials said.

But given the criteria Carter and other Pentagon officials laid out Wednesday, it’s far from certain that McLain and other wounded combat veterans will qualify for that debt relief.

Neither Carter nor his deputy, Peter Levine, the acting assistant secretary of Defense who will lead the review, indicated that they will make a blanket exception for soldiers who were wounded in battle.

Federal law already allows the Pentagon to waive certain debts for Purple Heart recipients. But officials haven’t granted that exemption to McLain and other Purple Heart recipients contacted by The Times.

Defense officials also said they don’t plan to waive repayment from soldiers who were ineligible for the enlistment bonuses because they already had served 20 years and thus were entitled to military pensions.

McLain joined the Army in 1979, later ending up in the California Guard. He retired in 2014 and resumed his job as a police officer with the Las Vegas school system.

McLain was born on a U.S. Army base in Germany. His father fought in Vietnam, his grandfather in World War II. He is proud of his military service in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But he and his wife are embittered and angry about the Pentagon demands for repayment of the incentives they gave him to go to war.

“Until we get a letter to us saying legally they can’t take us to [debt] collection or turn us over to the IRS, I won’t be satisfied,” he said Thursday.

Like many California Guard members, McLain’s bonus problems began in 2006, when he was serving in the 19th Special Forces Group, a National Guard unit based in Los Alamitos.

He had gone to Afghanistan in 2002 shortly after the U.S.-led invasion that ousted the Taliban from power.

Four years later, when his enlistment contract was expiring, he volunteered to go to Iraq as the Sunni Muslim insurgency against the U.S.-led occupation was reaching its most violent phase.

Instead of signing a new six-year enlistment, McLain opted to extend his old contract for the year he would deploy in Iraq, receiving no bonus.

He was assigned to a regular Army special forces team at an outpost near Hit, an Iraqi insurgent hotbed where U.S. troops were engaged in fierce daily combat.

McLain says that the unit’s senior noncommissioned officer told him that if he signed up for another six-year contract while in a war zone, he was entitled to a $30,000 reenlistment bonus since he was on active duty.

McLain says he was skeptical. He believed that as a California Guard member, he only qualified for $15,000, the usual bonus at the time.

But he signed the contract and within weeks received two extra payments of $7,500 in his paycheck. When the other money didn’t appear, he says he assumed he only qualified for $15,000 and “thought no more about it.”

His year in Hit, a sand-blown walled town on the Euphrates River northwest of Ramadi, involved near daily combat.

“Our job was to train the Iraqi police, and we went on a bunch of operations” aimed at capturing insurgents, he said. Militants ambushed U.S. convoys and regularly bombarded his unit’s small outpost with mortar fire, he said.

“By the end of that deployment I had been struck numerous times by IEDs and had been diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury,” McLain wrote in August 2015 in his bonus repayment appeal to the Pentagon, using a military abbreviation for improvised explosive device.

His injuries weren’t severe enough to require hospitalization.

A year after McLain returned to the U.S., in 2007, another payment of $7,500 appeared in his Army paycheck without explanation. Then another $7,500 arrived, for a total of $30,000 in bonuses.

“It just showed up on my paycheck, and I thought, ‘Great, he was right,’” McLain said, referring to the senior sergeant in Iraq who had told him that he qualified for $30,000.

McLain returned to Iraq in 2008 and fought in a major battle in the southern city of Basra, where U.S. and Iraqi troops had been sent to quell an insurgent uprising.

As he rode through the city one day, a powerful roadside bomb exploded near his vehicle. A small piece of shrapnel tore through the armor plating and hit the headset radio microphone that McLain used to communicate with other soldiers.

The impact drove his jaw back, bloodied his mouth and left most of his teeth loose. After he returned to Las Vegas in 2009, a Veterans Affairs doctor found his lower jaw was infected. He removed McLain’s teeth and performed a bone graft to reconstruct his lower jaw.

In January 2013, McLain received a letter from the California Guard telling him that he did not qualify for the $30,000 in bonuses he had received after reenlisting seven years earlier.

Since he had enlisted in 1979, the letter claimed, he had served more than 20 years in the Army when he reenlisted, and Pentagon rules barred giving bonuses to soldiers who had passed the two-decade mark.

Even if he had been eligible, as a member of the California Guard, he would have only received $15,000, the letter stated.

The bottom line: He had to pay back the entire $30,000.

McLain refused to pay, arguing that he had served only 17 years, because, after leaving active duty, he was inactive from 1988 to 1993 before joining the National Guard.

A week before he left for Afghanistan, the Pentagon sent him a salary statement for $0.00.

He has been fighting the debt ever since.

In 2015, when the Pentagon offered to give him a long-term repayment agreement, he crossed out a section that required him to admit he owed the debt, and started sending $100 checks.

The Defense Finance and Accounting Service, the Pentagon agency that handles repayment of debts, responded with a letter that said because he had “altered” the repayment agreement, he was required to immediately repay the entire $27,112.82 it said he still owed.

“We have determined that we cannot suspend your … debt any longer,” said the letter. It was signed by an unnamed “customer care representative.”

david.cloud@latimes.com

|